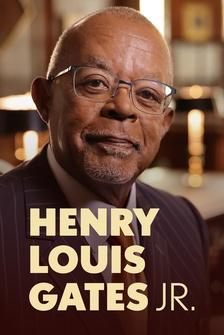

GATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots".

In this episode, we'll meet Bob Odenkirk and Iliza Shlesinger, two people who grew up trying to make their families laugh.

ODENKIRK: Uh, there's a photograph of me, looking calmly at the camera and my mom said, "That's the only picture where you're not being silly that exists of you."

SHLESINGER: My mother has told me this story, of, they had Groucho Marx glasses with the nose and the mustache.

GATES: Right.

SHLESINGER: My mom would put it on and she would point and she would say, "Funny."

And then, I guess, a family friend came over, who did look like that... big nose, mustache, glasses, and I pointed to him, and I said, "Funny."

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available... Genealogists combed through paper trails stretching back hundreds of years.

While DNA experts utilized the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

And we've compiled everything into a "Book of Life".

A record of all of our discoveries.

SHLESINGER: I can't believe you found this!

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

These are your immigrant ancestors.

ODENKIRK: Uh, I wanna shake their hand... And give them a hug and a kiss.

SHLESINGER: I feel a part of something and, like, complete.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: In, in a way that I didn't think I ever would 'cause I thought I had, like, six people in my family.

GATES: So what is it like to learn this?

ODENKIRK: The best.

Why am I so happy and proud?

GATES: My two guests have devoted their lives to comedy.

But their roots are filled with people who had a much simpler goal: survival.

In this episode, Iliza and Bob will meet ancestors who faced enormous challenges, and who made immense sacrifices to lay the groundwork for their success.

(theme music plays) ♪ ♪ (book closes) ♪ ♪ GATES: Bob Odenkirk became a star by accident.

In 2009, when he was in his late 40s, and best known as a sketch comic, Bob was cast as a sleazy lawyer named Saul Goodman on "Breaking Bad", the iconic AMC series about a high school teacher- turned-drug-dealer.

Saul was conceived as a supporting role, but he became one of the most memorable characters in television history, leading to a spinoff series of his own and making Bob a household name.

It's a heartwarming and extremely improbable, story.

But knowing Bob's own story helps make sense of it.

Much like Saul, Bob has seen his share of hard times.

Raised in an Irish-Catholic suburb of Chicago, He's the second of seven children, and he grew up telling jokes to his brothers and sisters in no small part to alleviate a deep pain in their lives.

ODENKIRK: There was a certain strain of, uh, tension in my home... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: Because my dad was an alcoholic... GATES: Oh, I'm sorry.

ODENKIRK: And he wasn't home very often.

Uh, and as the years went by very rarely.

I don't know how they had seven kids.

GATES: Right.

ODENKIRK: Figure that out.

But, uh, but he wasn't around much, and there was always a mystery of where is this guy and what's wrong?

Something's wrong.

We lived in a very nice town, Naperville.

Uh, but we didn't have a lot of money.

We drank powdered milk.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: So, it didn't make sense.

Like, "Why are we here if we don't have anything?"

You know, we don't, it was just strange and there was a tension there all the time.

GATES: Ah.

ODENKIRK: So, the humor was, for my brothers and sisters, for all of us, a way to lighten, lighten the load of, of the weird tension of this existential strangeness.

GATES: Bob would soon discover that his humor had an appeal that reached well beyond his siblings.

He was hired by "Saturday Night Live" as a writer when he was just 24 years old, and quickly won an Emmy.

Six years later, he co-created "Mr. Show", a wildly inventive sketch comedy series for HBO.

ODENKIRK: You're high.

(audience laughter) CROSS: No, no.

ODENKIRK: I smell marijuana on you!

CROSS: Well, check that... How about medical marijuana?

(audience laughter) ODENKIRK: You're not sick!

CROSS: It's for work-related stress.

ODENKIRK: "For stress related to working with Bob Odenkirk."

GATES: "Mr. Show" is still beloved today, but it never got the ratings it deserved.

And when it ended, Bob found himself adrift, searching for a new project to suit his skills.

Unfortunately, that search would last for more than a decade... ODENKIRK: I basically went into, I'm calling it, “Development Heck.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: Because, um, it was just numerous years of projects that sometimes made it to pilot stage where you'd shoot the pilot.

Many of them made it to, uh... uh, script stage where you'd get paid to write the script.

Um, and I call it, "Development Heck" because it wasn't really Hell.

I had kids.

I had some money coming in, a little.

Uh, it wasn't the worst thing in the world.

And I got to act here and there, little character roles that I would be offered.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: But it was hard, though.

Uh, that much failure is hard.

GATES: Did you ever think about quitting?

ODENKIRK: Well, see there's the thing.

At that point, what are you gonna do?

GATES: Right.

Bob's salvation came out of nowhere, when he was offered the role of Saul Goodman, he accepted it on whim, without auditioning, after barely reading the script.

He was slated to appear in just a few episodes, but his performance took everyone by surprise, transforming his life, and his career... As he discovered untapped talents as a dramatic actor.

ODENKIRK: I'm unbelievably grateful.

I'm unbelievably grateful.

I won the lottery.

GATES: You did, you did.

ODENKIRK: It's better than the lottery!

GATES: Right.

ODENKIRK: When you win the lottery, they give you a bunch of money and you go screw up your life with it.

GATES: Yeah, that's right.

ODENKIRK: I won this relationship to the industry that I loved and was attracted to.

GATES: You did.

Big time.

ODENKIRK: And I can't explain it.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: I don't deserve.

I didn't deserve it.

And sure there's some Catholic guilt in there, but also it's true.

GATES: Right.

ODENKIRK: If the audience decides, “We like you in drama.

I know you like sketch comedy, I'm glad you did it, thank you”" “But we like you in drama.” GATES: And you can say, "I'm cool with that."

ODENKIRK: Okay.

You got it.

GATES: My second guest is comedian, actor, and author Iliza Shlesinger... Iliza is renowned for her brilliant stand-up routines, which mix sly observational humor and biting social commentary.

SHLESINGER: You're like, "I don't wanna bring a jacket!"

"Why not?"

"Because then I have to carry it."

Girls hate the idea of having to carrying a jacket.

"It's too heavy."

The female body is capable of carrying a human being for nine months but apparently a light-weight jacket stuffed with feathers is where we draw the line.

GATES: Much like Bob Odenkirk, Iliza told me that her comedic talents were forged in her childhood home, but Iliza comes from a very different kind of home.

Her parents were Jewish New Yorkers who moved to Dallas, Texas when Iliza was a child, compelling their daughter to grow up in a world where she was always something of an outsider.

SHLESINGER: We lived in a normal... Like, I took a school bus, not a horse.

Like, we lived in a normal suburb.

GATES: Right.

SHLESINGER: We belonged to a synagogue.

Like, there are a, I know, especially now, a lot more Jews in Dallas... GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: But you still were, like, a little "other than" growing up.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Like, they had, like, Fellowship of Christian Athletes, and... there never was nor has been a Fellowship of Jewish Athletes at a public school.

So, yeah.

GATES: In Black culture, there's always a day, you know, when you realize that you're Black, and that it's not a good thing for a lot of people.

Did that happen to you, in terms of antisemitism?

SHLESINGER: Yes.

I remember, uh, one of my best friends when I was little, who, we're not gonna name names, um, she said something bad to me.

So, my mom, as moms do, called her mom.

And she said, "You know, your daughter told my daughter, Iliza, that because she's Jewish, she's gonna go to hell."

GATES: Uh-huh.

SHLESINGER: 'Cause this is what you're taught... GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: In some branches of Christianity... GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: You know?

And the mother, rather than saying, "Oh, I'ma have to talk to her.

That's not right," she said, "Oh, I'ma have talk to her.

She's not supposed to start witnessing 'til she's older."

GATES: Oh my God!

SHLESINGER: So, there's that, and then it's not so much, like, it's not violent antisemitism, but, um, you know, ask, like, hearing things, like, "Do you drink babies' blood or eat babies?"

Or "Do they have horns?"

And things like that.

And it's just things that you're aware of, and you're aware of how the world, especially as you get older, views Jewish people.

And of course, these things are also hurtful, but I do think it teaches a modicum of compassion in terms of dealing with other people's struggles in life.

GATES: Though Iliza may have felt out of place, she immersed herself in her new environment with an impressive amount of confidence, guided by a single-minded ambition to somehow become a comedian.

There were no performers or artists of any kind in her family, but her parents encouraged her just the same.

And when she got to high school, she joined an improv troupe, despite the fact that there were no other women in the group.

You were the only girl in the improv troupe, right?

SHLESINGER: Yeah, for a while.

GATES: What was that like?

SHLESINGER: It's so funny.

I never... there's a big conversation nowadays around, like, woman, women in comedy.

And younger people act as if there haven't always been women in comedy.

We've been here for a minute.

Like, we've been here since the beginning.

Perhaps not as celebrated, not as visible, but women have been doing this.

And, uh, because, growing up, feminism wasn't as huge, wasn't as big of a conversation as it is now, certainly wasn't as ubiquitous, we definitely didn't have the internet, and women in comedy wasn't such a sticky topic... GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: I was never told women aren't funny.

GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: And boys liked to be around me because I was funny, and my friends, like, that was my currency.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: For some people, it's their looks.

Some people it's that you're the person you want in science lab to sit next to.

That was my thing.

And so, I never, it never occurred to me that I wasn't just as funny, if not better.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: So, this idea that I would be a shrinking violet or that boys should go and girls shouldn't, I just went and I remember thinking, we were, like, at improv practice, I remember thinking, like, they were all messing around, and I was like, "You guys are gonna go and have normal jobs.

I'm gonna do this for a living, so, pay attention because we only have 30 minutes before lunch."

(laughter) GATES: Iliza knew what she was talking about, and her determination paid off big time.

Today, she's more than "making a living" at comedy, she's a headlining act with a global fanbase, and six Netflix specials to her name...

But even so, Iliza readily acknowledges that her abilities only took her so far.

She also needed a bit of luck.

Especially when she first moved to Los Angeles and tried to launch her career.

SHLESINGER: I didn't know anything about the industry.

And I remember thinking, like, like every wide-eyed girl coming to LA, like, "If I can just get on a stage, they'll see how great I am."

GATES: Right.

SHLESINGER: How do you get stage time if you don't know anyone?

I saw an ad, must've been in a paper or online, for a school.

It was called The Judy Carter Comedy School.

GATES: Huh.

SHLESINGER: I saw in the ad that at the end of the classes, you get a showcase.

GATES: Hmm.

SHLESINGER: Everybody who took the class gets up and they do their five or so minutes.

And I thought, "Well, that's how I'll get my stage time.

I'll, I'll take these classes, I'll earn the showcase, I'll do it.

The President of Comedy will see me, and that will be that."

So I started taking the class, and I met another comic.

This, another man, his name was Tim Powers, super nice guy who's, like, a father and taking this class.

GATES: Hmm.

SHLESINGER: And I became friends with him, and he was a real live standup comic.

And while we became friends in the class, he was like, "You know, my friends and I, we do comedy at a bar in Hollywood.

Why don't you come on by?"

GATES: Ah, that's great.

SHLESINGER: And so I went.

GATES: Huh.

SHLESINGER: I went at 22 to this bar, and there's like a bunch of grown men that put on a standup show and they gave me time.

So I cobbled together my few jokes that I had written, uh, and my one-man show from college and a couple of other things.

And I invited my friends, as you do, and, and, and it was great.

GATES: Huh.

SHLESINGER: Not great, it was, it was whatever.

I think there was a joke about herpes, a joke about LA traffic, whatever, and they invited me back.

GATES: Huh!

SHLESINGER: And it's a real sink-or-swim moment, and I just decided to swim.

GATES: Iliza and Bob have been fortunate.

Their comedic gifts have brought them a level of success that they could never have imagined when they were young.

Now it was time to introduce them to ancestors whose gifts were decidedly more practical, and whose lives were more inclined towards drama than comedy.

I started with Bob Odenkirk, and with his mother, Barbara Baier.

Barbara anchored Bob's childhood home, driven by an inner warmth that, for whatever reason, seemed to elude Bob's father.

ODENKIRK: He was a mystery to me, and my dad is a mystery to me.

Well, he left the house when I was 15, and I met him again when I was 22 when he was dying.

GATES: Oh.

ODENKIRK: And, uh, we got to meet probably five or six times and I could never sort it out.

I just could not figure that guy out.

GATES: Hmm.

ODENKIRK: I don't know what his deal was.

My mom was the core of our lives.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: She, uh, loved having kids.

She loved raising kids.

She was supremely busy.

She told me, "One day I did 15 loads of laundry."

GATES: Wow.

ODENKIRK: Uh, she was happy doing that.

GATES: Hmm.

ODENKIRK: Um, kids entertained the heck out of her.

She laughed at our antics all the time.

She never laughed harder than we, when me and my brother Steve would start to fight, physically fight, which we didn't do often.

But four times, maybe, in our lives, we went at each other and she, nothing killed the fight more than my mom cracking up as hard as she did.

GATES: Bob came to me knowing that his mother has extensive roots in Ireland, and he told me that he grew up feeling deeply attached to that side of his ancestry.

But we discovered that his mother also descends from a man who wasn't Irish...

The story begins with the 1870 census for Chicago, where we found Barbara's great-great-grandfather, a French carpenter named François Fricker.

ODENKIRK: So I'm part French.

GATES: You're part French, without a doubt.

Did you have... ODENKIRK: Never heard anything... GATES: Any idea you had French?

ODENKIRK: No!

No!

Nothing!

Oh, I wish my mom could hear this.

She would've loved this.

GATES: We don't know what drove François to immigrate, but records show that he left France sometime around 1853, and that his wife and their five children came over the following year, after auctioning off their home and virtually all of their possessions, likely to pay for their passage... GATES: These are your immigrant ancestors.

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

GATES: These are the people who brought this part of your family to America.

What's it like to meet them?

ODENKIRK: Uh, I wanna shake their hand and give them a hug and a kiss.

Uh, it's moving because I...

I'm so thankful for the sacrifice that these people made.

And if they could see what I've been given, this gift of this career and, and the people in my life, I think they'd be so proud, and I have them to thank for it.

GATES: They would be very proud, buddy.

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

They'd also be like, "What's a movie?"

GATES: Francois and his family undoubtedly endured great hardships on their journey to America.

But moving back one generation, we came to a man who endured even more.

Francois' father, Jean Jacques Fricker, was born in 1790...

He's Bob's fourth great-grandfather, and we found military records, showing that he was mustered into the French army in March of 1809, when he was still a teenager.

ODENKIRK: It's so wild.

It's so wild.

GATES: And why is he going into the army?

You want to take a guess?

ODENKIRK: He stole something.

GATES: No, no.

Close.

Napoleon stole something and was about to try to steal more.

It was the Napoleonic Wars.

ODENKIRK: Right.

GATES: By 1809, Napoleon had been Emperor of the French for five years, and had already fought several wars across Europe.

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

GATES: Conscription was a requirement for all young men in the French Empire.

Otherwise, they would be considered deserters and bad things would have happened to them.

ODENKIRK: Wow, so... GATES: So your fourth great-grandfather didn't have much of a choice.

ODENKIRK: Yeah, Napoleon said, "Let's go.

Show up."

GATES: He said, “Let's go.” He was 18 years of age.

Can you imagine going off to war at the age of 18?

ODENKIRK: Yeah, back then with, I mean, anytime, but that was blood and guts, man.

GATES: Bob is correct... his ancestor would see "blood and guts" very quickly... At the time, Napoleon had grand ambitions, and was determined to dominate all of Europe.

In early May of 1809, he captured Vienna, the capital of Austria, and then set out to crush Austrian armies that lay just across the Danube River on the opposite shore.

But that's where Napoleon's luck took a turn for the worse.

ODENKIRK: "The French army, commanded by the Emperor Napoleon in person, has been totally beaten at Aspern and Essling by the Austrian army.

On the 22nd at 4:00 a.m., the Emperor thought the decisive moment was come and ordered his cavalry to charge and support the infantry, but the repeated charges of the cavalry could not pierce the center.

The Emperor Napoleon, perceiving that his communication was threatened, hastened his retreat, leaving on the field of battle a great number of dead and wounded."

Don't follow crazy people into war.

GATES: Your ancestor was there.

ODENKIRK: Wild.

GATES: What's it like to insert yourself in world history?

ODENKIRK: Well, you see paintings like this all the time.

GATES: Yeah, that's right.

ODENKIRK: You don't think, “Oh, that's my great-great-great-great- grandfather right there.” GATES: No.

ODENKIRK: But it is.

It's somebody's great-great -great-great-grand father.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

The battle was Napoleon's first major defeat in over a decade and it was a bloodbath for the French army, which suffered more than 20,000 casualties in two days of near-constant fighting.

ODENKIRK: Wow, I'm surprised anybody survived at all.

GATES: Please turn the page.

ODENKIRK: This is an amazing saga that I had no sense of.

GATES: This is another page from your fourth great-grandfather's pension file.

Would you please read that translated section?

ODENKIRK: "Jean Jacque Fricker is unable to continue his services because of a gunshot received on May 22, 1809, which caused him to lose the little finger of his right hand, as well as the free use of the ring finger.

The adherence of the scars deprives the hand of its free movements."

Uh, get out of jail free.

Uh, get out of here, not free.

GATES: No.

ODENKIRK: You lose your hand, you know.

GATES: He was only 18 years old.

Can you imagine being physically scared for the rest of your life at the age of 18?

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

Yeah.

In a time when manual labor was, was work.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: Was what you could do, all you could do, in a lot of places, and you can't use your right hand.

Devastating.

Devastating.

GATES: Jean was discharged from the army with a small pension.

He managed to find work as a police officer, and settled down to start a family.

But a great many challenges lay ahead.

In 1813, when he was just 23 years old, Jean's wife died in childbirth.

He would remarry, only to see his second wife, Bob's fourth great-grandmother, succumb to a protracted illness and soon after, Jean himself would reach a tragic end.

ODENKIRK: “Jean Jacques Fricker, aged 53 years, died in this town on the 5th of November, 1843 at 2:00 in the afternoon near Wayer's Tile Factory.

Cause of death: drowned.” GATES: Drowned.

Your fourth great-grandfather drowned, sadly, at the age of 53.

He had survived the Napoleonic Wars, lost a wife and child in childbirth, then lost another wife, and then he drowned.

ODENKIRK: I want to say...

I'm sorry your life was so hard and it ended so, with so much pain.

But so much good came from you being tough, and... And having kids, and sticking around.

GATES: What does having this information restore to you?

What is it doing to you?

Does it change the way you're seeing yourself, Mr. Frenchman?

ODENKIRK: Yeah, never thought I connected at all to that country.

But, uh, all those people in those paintings, all those people you read about, those are our great-great- great-great-grandpas and grandmas.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: And they paid the price, and straggled forward, and, uh, lost a lot, and I'm part of that and it's...

It makes me feel connected to people.

GATES: Yeah.

ODENKIRK: To the world.

GATES: Just like Bob, Iliza Shlesinger was about to discover a hidden connection to an ancestor whose story had been forgotten.

Her father, Fred Shlesinger, was born in Amityville, New York in 1955.

Iliza knew that his roots lay in Eastern Europe, but that was all she knew.

We began to reconstruct those roots by focusing on Fred's grandparents, Iliza's great-grandparents, Morris Schlessinger and Esther Shonek.

SHLESINGER: Oh, man.

Oh, man.

These people don't look like me.

But it's also black and white.

But I think they have very dark hair, which I secretly do.

Don't look at my roots.

GATES: Growing up, did you hear any stories about them?

SHLESINGER: Yes, I heard that they were, like, a lovely couple, incredible couple.

It was, like, a loving household.

Everybody loved them.

And I think they spoke, one of 'em spoke Russian.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Or is it German?

GATES: Or Yiddish.

SHLESINGER: Or Yiddish.

That's a given but I feel like one of them, were they both born, oh, you don't know...

Were they both born in New York?

GATES: We're gonna get there.

SHLESINGER: Okay, so then, I guess I don't know a lot.

I just know that my dad loved his grandparents.

GATES: Well, let's see what we were able to find.

Would you please turn the page?

SHLESINGER: Okay!

This is so cool.

GATES: We're back to 1940.

This is a page of the United States Federal Census for Brooklyn, New York.

SHLESINGER: Okay.

GATES: Would you please read the transcribed section?

SHLESINGER: Oh, here's the real spelling of Shlesinger.

"Morris Schlessinger..." GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: With a C and a double S. GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: “Head age, 42.

Occupation, clerk at a fish store.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: “Esther, wife.

Age, 38.

"Benjamin," my grandfather, "son, age, 16.

Sarah, daughter.

Age, 10.” GATES: There's your grandfather and his younger sister, Sarah in the household of their parents, your great-grandparents, Morris and Esther.

SHLESINGER: Okay.

GATES: At the time, take a look there, the family lived in Brownsville, which is a neighborhood in eastern Brooklyn.

And that's a photo of their house, right there.

SHLESINGER: Oh my God.

Wow!

That's cool.

I can't wait to show my dad.

GATES: This census indicates that Morris and Esther were born in Poland.

But as we dug deeper into the couple's shared past, we were able to learn much more about their origins.

SHLESINGER: "Certificate and record of marriage.

Groom, Morris Schlessinger.

Age, 27.

Occupation, metalworker."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Eh.

"Birthplace, Plock, Russia."

GATES: Yeah, you go it.

SHLESINGER: "Father's name, Abraham."

"Mother's maiden name, Ida Beckerman."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: "Bride, Esther Shonek."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: "Age 21."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: "Birthplace, Plock, Russia."

Wow!

GATES: And I'm sure you've heard of Plock.

SHLESINGER: Well, I summer there.

So, it's weird that I don't know this already.

GATES: Plock is a city in modern-day Poland.

When Iliza's ancestors were born, it was part of the Russian Empire... War and the holocaust devastated this region during the 20th century, and many records were lost or willfully destroyed.

Indeed, it's often impossible for us to learn anything at all about the Jewish people who lived here, but with Iliza, we got lucky.

SHLESINGER: "In the town of Raciaz, on the 25th of April 1900 came Jankof Josek Szonek, 32 years old, a merchant, and presented to us a female child, stating that she was born in Raciaz on the 15th of January, 1899.

The child was given the name Estera Blima.

The lateness of this declaration is the fault of the father."

Okay, what did I just read?

GATES: This is the birth record for your great-grandmother Esther Sjomek from the year 1900.

SHLESINGER: Wow!

So, my dad's dad's mother.

GATES: Yup.

What's it like to see that?

SHLESINGER: I guess I thought nothing like this existed.

GATES: Mm.

SHLESINGER: Because my dad and my uncle didn't know, so I was like, "I guess I'll just never know."

GATES: This record indicates that Esther was actually born in Raciaz, a small town about 30 miles northeast of Plock.

And learning this fact proved a gold mine to our researchers, allowing us to uncover a "residents book" for Esther's hometown that describes her childhood household in great detail.

SHLESINGER: "Chaim.

Son.

Born December 8th, 1896.

Estera Blima", ah, she has a brother!

"Daughter.

Born January 15th, 1899.

Joel Lipa, Son."

Ah, another one!

"Born August 13th," Oh my God, there's so many!

"August 13th, 1901."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: “Abram.

Son.

Born September 14th, 1904.

Itzek.

Born December 16th, 1907."

God, you couldn't give her a break?

"And Rivka.

Daughter.

Born December 16th, 1907."

GATES: So, twins.

SHLESINGER: They're twins.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

(gasps).

Had, had you ever heard any of those names before?

SHLESINGER: No.

No idea.

GATES: Any idea that she came from such a large family?

SHLESINGER: None, none, and twins, too!

GATES: And twins too, which is pretty cool.

SHLESINGER: Yeah.

GATES: What do you think their life was like?

SHLESINGER: Well, he was a merchant.

Probably super simple.

Or probably just your garden-variety Polish peasant.

Probably had just a small house.

Maybe like, a horse.

I don't know.

GATES: Iliza's guesses are most likely accurate.

When her ancestors lived in Raciaz it was part of what was known as "Congress Poland" which bordered and shared practices with the notorious "Pale of Settlement", where Jewish people were confined and oppressed by the Russian Empire.

Jews in the region were subjected to an array of humiliating restrictions, forced to pay additional taxes, and generally denied access to higher education.

Most ended up as tradespeople, struggling to get by, and Esther's family was no exception.

Which led her to make a radical decision.

SHLESINGER: "Esther B. Sjomek.

Age, 22.

Occupation, dressmaker.

Last permanent residence, Poland.” GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: "By whom was passage paid?

Self."

Yes!

"Where they're going to join a relative, Uncle Frank.

59 Pitt Street, New York."

GATES: So, you know what you're looking at?

You just read the moment your great-grandmother Esther stepped foot in the United States.

SHLESINGER: Wow.

Wow!

GATES: That is her moment of arrival.

SHLESINGER: Ah.

GATES: What it like to see that?

SHLESINGER: That's like...

I'm like emotional.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Because she did that all by herself.

GATES: All by herself.

SHLESINGER: She left her whole family.

GATES: She was 22 years old when she made the journey.

SHLESINGER: Oh my God.

GATES: And she made it all by herself.

SHLESINGER: Yeah.

GATES: And guess what?

She paid for her own ticket.

SHLESINGER: She paid for her own ticket.

She saved up money and she did it all by herself.

GATES: Yup.

SHLESINGER: Wow GATES: So, what does this tell you about your ancestor?

SHLESINGER: That she had dreams for herself that extended beyond her small village.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Uh... GATES: Yeah, "I'm outta here."

SHLESINGER: Yeah!

And to leave your family behind, obviously very difficult but she wanted more.

And I don't know what that conversation was but she definitely was like, "If you're not gonna help me I'll do it myself."

Or they couldn't so she did it herself.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Wow.

That's very cool.

GATES: We'd already traced Bob Odenkirk's maternal roots back to Napoleonic France... Now, turning to his father's ancestry, we were able to go even further into the past, moving from his grandfather Walter Odenkirk back five generations to a man named Friedrich Carl Steinholz... GATES: You just met your fifth great-grandfather.

Your great-great- great-great-great grandfather.

ODENKIRK: 1755!

GATES: Isn't that amazing?

ODENKIRK: That's unbelievable.

Wow.

Wow.

GATES: Friedrich Carl Steinholz was born around November 30th, 1755, near Plön, a town that is in what is now Germany.

There you go.

ODENKIRK: I see.

GATES: You can see it.

ODENKIRK: Plön.

GATES: Yeah.

And Plön is about 60 miles north of Hamburg.

ODENKIRK: Right.

GATES: Ever been to Hamburg?

ODENKIRK: Uh, no.

I've never been there.

GATES: Let's see what we found out about your ancestors' lives back in good old Plön in the 18th century.

ODENKIRK: Wow!

GATES: We found this record in church archives in Germany.

It's dated 1778, Bob.

Would you please read the translated section?

ODENKIRK: Yes.

“Marriage, 12 June, 1778.

Friedrich Carl Steinholz, bachelor of Plön, now living in Heuerstubben and Lucia Amalia Hammer, daughter of the city council member in Heiligenhafen, Johann Heinrich Hammer and his wife Engel Catharina Wittrock.” GATES: That is your fifth great-grandparents marriage record.

Isn't that wild?

ODENKIRK: Yeah, that's wild.

It's so long ago.

GATES: Curiously, Bob's 5th great-grandfather Friedrich Carl did not list his mother, a woman named Marie Catharina Bein, on his marriage record...

Nor did he list his father.

This sent our researchers into the archives of Plön, where they found Maria's death certificate, and discovered a family secret.

ODENKIRK: “Maria Catharina Bein, although she died unmarried, still she leaves behind from her former relationship with the last deceased Duke of Plön”, Get out of town, “The following children.” Wait.

She wasn't married?

GATES: Keep reading.

ODENKIRK: "But she leaves..." She did have a relationship with the Duke of Plön?

GATES: With the Duke of Plön.

ODENKIRK: “The following children.

Her deceased daughter, Maria Carolina Steinholz, Friedrich Carl Steinholz, Christian Carl Steinholz, August Wilhelm Steinholz.” GATES: Yes.

ODENKIRK: I am descended from the Duke of Plön?

GATES: Your sixth great-grandfather was a duke.

ODENKIRK: What?

Oh, man.

That's so great.

GATES: The Duke of Plön was a member of Europe's aristocracy.

He owned several magnificent homes, as well as a castle.

But though he had four children with Bob's 6th great-grandmother, he did so while married to another woman.

GATES: So you know what this means?

ODENKIRK: Well, she was the mistress.

GATES: She was the duke's mistress.

ODENKIRK: And you just did that?

GATES: He was the duke, man.

He was 20 years older than she.

ODENKIRK: Right, he's a, you know... GATES: Sources vary on how they met.

You know, the story of the relationship has been written about.

ODENKIRK: Really?

GATES: But it seems as though she either worked for or knew someone at the duke's court.

So isn't this wild to think that you descended from a duke and his mistress?

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

It is just... That... that time in history, royals and things, it's just so distant to an American.

GATES: Bob worried about the nature of the relationship between his ancestors, especially given the enormous power disparity that separated them...

Though we can't be certain how Bob's 6th great-grandmother Maria perceived matters, we found what is known as a "Marriage Promise", actually written by the duke... and it articulates his feelings, in very plain language.

ODENKIRK: “We, Friedrich Carl, after having united ourselves with the virgin, Maria Catharina Bein, in such a way that we both want to live together for the time being, to remain faithful, to be inseparable, to part with nothing but death, and to prove all sincere love.

And in order to fully convince her of our sincere intentions."

Really?

Do that, wow, “To promise fully on oath that should the Lord demand our spouse from this world, we shall take the maiden, M.C.

Bein, to us immediately, to recognize, accept, and adopt her as our spouse, and to take care of her after our possible death, as it will then come to her.

Signed with our own hands and sealed with our princely seal, Friedrich Carl.” GATES: Your sixth great-grandfather, the duke... ODENKIRK: Loved her.

GATES: He probably, he loved her.

ODENKIRK: Absolutely.

GATES: And he promised to marry your sixth great-grandmother, his mistress... ODENKIRK: And he wrote it down.

GATES: If his current wife died.

ODENKIRK: Yeah, you would write something like this.

What about his current wife being like, "What did you sign?

What?"

"I saw something came in the mail.

You're talking about my death?

I'm here.

I'm right here."

GATES: We have no idea how the duke's wife felt about his promise, but in the end, it didn't matter.

Seven years after setting down his intentions, the duke passed away, and his wife survived him.

So Bob's sixth great-grandparents never married.

ODENKIRK: Amazing.

GATES: Does seeing that change the way you think of your ancestor, the duke?

ODENKIRK: Sure does.

GATES: He promised to marry.

ODENKIRK: It, it, it sure does.

GATES: Yeah.

ODENKIRK: He didn't just bonk this woman and have fun... GATES: Right.

ODENKIRK: And run away.

GATES: Right.

ODENKIRK: Yeah, no, he loved her.

GATES: He loved her.

ODENKIRK: Yeah, and so, yeah.

GATES: Please, please turn the page.

I want to... ODENKIRK: There's another page?

GATES: I want to show you something else.

ODENKIRK: This is crazy.

What?

GATES: That is he.

Your sixth great-grandfather, the Duke of Plön.

ODENKIRK: Wow.

GATES: Any family resemblance?

ODENKIRK: I have very wide-set eyes and a tiny puckered mouth and a chubby chin.

No.

Uh, the hair, uh, losing his hair.

Um, yeah.

There is.

Yeah.

Yeah.

To my grandpa Odenkirk.

GATES: Yeah?

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

In the face and the eyes.

GATES: There you go.

ODENKIRK: Dude, right... GATES: Yeah.

ODENKIRK: This guy.

GATES: There you go.

ODENKIRK: Those eyes.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: Yeah.

That's wild.

Dude, that is wild.

He looks like an Odenkirk, in the eyes.

And the chin, and the chin.

GATES: Though Bob's inheritance from the duke may be limited to facial features, there's another dimension to their relationship.

The duke's title links Bob to the royal families of Europe, including Charles III, the King of England, as well as the former monarchs of Denmark and many other nations.

ODENKIRK: That is wild.

GATES: Bob, how does this make you feel?

ODENKIRK: Uh, like I'm part of history... GATES: Mm-hmm.

ODENKIRK: That I didn't think I was any part of.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

Right.

ODENKIRK: But I'm an American.

I'm not a monarchist.

I don't believe in, uh, that.

You know, I feel like it's a little twisted.

I understand why society built itself around monarchs and leaders, and they passed them down through generation...

I understand that goes through every society, every civilization, but um, I think that we've gone to a better place with democracy, and we should keep going down that road.

GATES: Really?

ODENKIRK: I do, yeah.

GATES: Well, guess what?

ODENKIRK: Uh-oh.

What's wrong?

What happened?

GATES: You and, you and King Charles III are 11th cousins.

(laughter) ODENKIRK: Well, maybe I'll change my mind on that.

GATES: Through the duke, you and King Charles III are 11th cousins.

Now, there you be trashing your family.

How they make a living.

You oughta be ashamed of yourself.

You ain't been royal born in five minutes and you complaining.

ODENKIRK: It's so funny, man.

Oh, that is crazy.

I never even thought about that.

Of course, that's true, right?

GATES: Yeah, 'cause all they did was... ODENKIRK: 'Cause all these families are related.

GATES: All they did was, all they did was marry each other.

ODENKIRK: 11th cousins.

GATES: 11th cousins.

We'd already traced Iliza Shlesinger's paternal roots from Poland to New York, showing how her great-grandmother Esther came to America in 1921 all on her own.

Now we turn to a tragic side of this story...

When Esther immigrated, she left five siblings behind.

And they would soon face an unimaginable ordeal.

On September 3rd, 1939 the German army entered the Polish town of Mlawa where Esther's brother, Lipa was a textile dealer.

Within a year the towns Jewish population was confined to a walled-in ghetto, This is never talked about in your family?

SHLESINGER: No.

GATES: Okay.

Now you have a younger brother, Ben.

SHLESINGER: I do.

GATES: What do you imagine it must have been like for Esther, knowing that her sibling was in so much danger?

SHLESINGER: Horrific.

I can't...

I know that feeling when your sibling's in danger and you feel helpless, especially from like an ocean away.

So I can't begin to imagine this.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Hmm, I don't think I want to.

GATES: Could you please turn the page?

SHLESINGER: Sure.

GATES: That is the Mlawa ghetto.

SHLESINGER: Hmm.

Yeah.

GATES: What's it like to see that, to think that you had a relative who, who was there?

SHLESINGER: Uh, you almost, when you look at pictures from history of atrocities committed against your people, in particular, there's always that pull.

But I never...

I never thought I had any actual connection because I didn't know any of the history.

GATES: It was abstract.

SHLESINGER: Yes, so I have to, like, sit with that.

GATES: I understand that.

SHLESINGER: Yeah, of course.

GATES: The Mlawa ghetto was essentially a death trap.

Residents had to live in pigsties and barns, and in November of 1942, transports began leaving for Auschwitz, where Esther's brother would meet a terrible fate.

SHLESINGER: "Lipa Szonek, Jewish religion, resident of Mlawa passed away on the" 'passed away', "On the 11th of January, 1943 at 12:45 in Auschwitz.

The deceased was born on the 15th of July in 1901 in Raciaz Cause of Death: myocardial degeneration."

GATES: What's it like to learn that you do, in fact, have a tangible blood connection to the Holocaust?

SHLESINGER: Ooh.

It was already so real.

And so now it's, uh, palpable.

You already feel that, uh, in a... You already feel it so much.

And, like, it's like a, a horrific missing piece.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: Then of course you read something like this and you're like, why is there even, like the fact that there was even a doctor?

'Cause they, you're murdered.

GATES: Right.

SHLESINGER: Your heart didn't degenerate.

Of course, it degenerated 'cause you were starved and... GATES: Sure, of course.

SHLESINGER: You were murdered.

I can't believe these monsters even wrote it down.

GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: But because they're psychotic, they wrote everything down.

GATES: And remember your great-grandmother, Esther, is alive in America at that time.

SHLESINGER: I mean, I guess we're all alive because someone was lucky.

GATES: Right.

SHLESINGER: You know?

GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: Wow.

That's just so hard to look at.

Even if it wasn't my family, like these things are always very painful and hard to read.

GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: Okay.

GATES: We now set out to see what happened to Esther's other siblings.

We discovered that her brother Abraham left Poland in 1931 and settled in France, where he married and started a family.

But that didn't guarantee his safety.

Nazi Germany invaded France in 1940, and the country soon faced the same horror as Poland.

Roughly 20% of France's Jewish population was exterminated.

So we wanted to see what happened to Abraham and his family.

Please turn the page.

SHLESINGER: I don't think I want to.

GATES: Iliza, this is a passenger record for a list of passengers who arrived in New York from France in November of 1955.

Abraham survived the Holocaust.

SHLESINGER: Okay.

GATES: What's it like to learn that?

That's the good side of the story.

SHLESINGER: Yeah.

GATES: I know you thought, “Oh my God, he's gonna take me through Auschwitz again.” SHLESINGER: I was like, “I don't wanna hear.” GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: Okay, wow.

GATES: Can you imagine Abram and Esther's reunion?

SHLESINGER: Oh wow.

GATES: Oh my God.

SHLESINGER: Haven't seen each other in what, since she was 22, so... GATES: Yeah.

SHLESINGER: And to know that they lost at least one sibling that I know of as of now.

Wow.

Wow.

GATES: According to one of Abraham's daughters, his family survived the war by hiding with a French farmer... Ironically, Iliza's grandfather Benjamin joined the United States Army during World War II and was stationed in France.

Meaning that he was unwittingly close to the site of an enormous family tragedy.

Do you think he knew he had immediate family in occupied Poland?

SHLESINGER: I don't know.

GATES: Relatives who are being locked in ghettos and dying in concentration camps?

SHLESINGER: I don't think he did because no one ever said anything.

Like why wouldn't you say that to your family?

My Nanna never, I mean that's her husband, but no one ever said anything.

GATES: Hmm.

SHLESINGER: Maybe he didn't know.

GATES: Maybe.

SHLESINGER: Oh, he didn't know.

And he was in France.

GATES: And he was in France too.

SHLESINGER: Wow.

What a complex thing.

GATES: Yeah.

Contingency, accident.

SHLESINGER: Yeah.

GATES: Just you make a choice, have no idea.

Unintended consequences.

SHLESINGER: Sure.

GATES: Unintended consequences of leaving, unintended consequences of staying.

SHLESINGER: Because some stated they were okay and then to have a relative be there, fighting for what's right while.

I mean, it's happening in just two different worlds right next to each other.

GATES: Right.

The complexities of war playing themselves out in the drama of one family.

SHLESINGER: Yeah.

GATES: What's it been like for you to learn about your father's family in this kind of detail?

SHLESINGER: Mind-blowing, because I didn't know any of this and I don't think my dad knew any of this, and he's kind of like the last of his family.

At least I thought.

I don't know what the kids that these people went on to have, but I always thought I had a very small family that like almost came out of nowhere.

GATES: Mm-hmm, mm-hmm.

SHLESINGER: And it's such a gift to be given any family history, just so you can kind of figure out your place in time in the context of all these people who were brave and who died.

It's incredible.

GATES: The paper trail had run out for Iliza and Bob.

It was time to show them their full family trees... ODENKIRK: Oh... My... God!

GATES: Now filled with names they'd never heard before.

(gasps).

SHLESINGER: Oh my God!

GATES: For each, it was a moment of awe.

ODENKIRK: Wow.

GATES: He is your 43rd great-grandfather.

ODENKIRK: That is insane!

GATES: Offering the chance to see how their own lives are part of a larger family story.

SHLESINGER: This is crazy!

ODENKIRK: Thank you so much for this.

I can't wait to share this with my brothers and sisters.

SHLESINGER: I get to show this to my daughter.

Oh my God.

GATES: My time with my guests was running out, but we had one more surprise for each of them...

When we compared their DNA to the DNA of other people who've been in this series, we found matches for both, evidence of genetic cousins they never knew they had.

For Iliza, this meant a new connection to an old friend.

SHLESINGER: Oh, my God, really?

GATES: Sarah Silverman.

SHLESINGER: I saw her the other night.

GATES: You and Sarah share long identical segments of DNA on your 2nd, your 10th, your 17th and your 19th chromosomes.

SHLESINGER: Okay.

GATES: So you have, this is a lot.

Usually, we establish a DNA cousin connection with identical shared DNA on one chromosome.

SHLESINGER: Right, wow.

GATES: And you shared on four chromosomes.

That is a lot of sharing.

SHLESINGER: My first thought was, like, "But she's from New Hampshire."

GATES: She's from... SHLESINGER: Oh my God.

GATES: She's from the Pale of Settlement.

That's where all this is from.

SHLESINGER: Yeah, yeah.

That's really cool.

GATES: Bob Odenkirk's new cousin shares his Irish heritage, as well as his comedic talents.

ODENKIRK: Oh my God!

Nathan Lane!

Are you kidding me?

GATES: No.

ODENKIRK: That's insane!

GATES: Nathan shares a long identical segment of DNA with you on chromosome 19.

ODENKIRK: You know, I'm gonna say, he looks a little like me.

He's got the eye thing that drifts down.

He's got some good warmth in his cheeks, a nice, big smile.

GATES: And he can act.

ODENKIRK: And he can act.

Yeah, he sure can.

Unbelievable.

That is the greatest.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Bob Odenkirk and Iliza Shlesinger.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of, "Finding Your Roots".